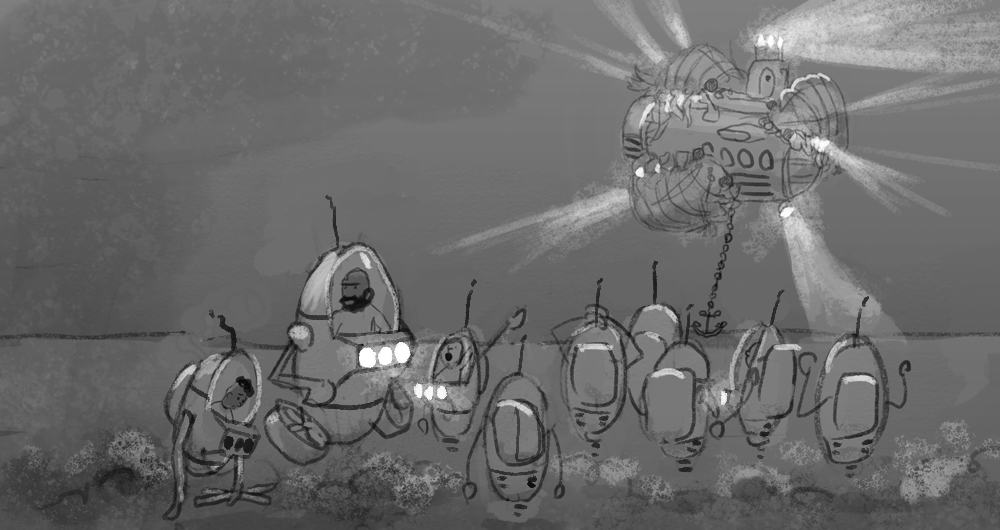

Figure 1: The third Field Trip already is in the works – this time the school class goes on excursion with an helicopter. (Source: John Hare's blog, 22.03.2021)

Helena Geisler: Dear John, you used to be a graphic designer before launching your successful career as an author-illustrator of wordless picture books. Your first publication, Field Trip to the Moon, published in 2019, has received a lot of attention, certainly in part because of the anniversary of the moon landing. In Germany, this poetic story about drawing, exploration and friendship was nominated for one of the most important children's and youth literature award, the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis, and you won the Rattenfänger-Literaturpreis.

Your most recent picture book Field Trip to the Ocean Deep has just been released in Germany. Therein you show us a colorful and mysterious underwater world. In your blog you write that you just finished the illustrations for your third Field Trip book, and apparently you are also working on a picture book with text! I am happy to be able to ask you a few questions about your working methods and your intentions in illustrating children's books.

You used to work as graphic designer, your website features some comics, and you also share illustrations that were created in the context of ‘painting parties' with friends. How did you come to illustrate wordless picture books for children? Or do they just accidently catch the interest of children?

John Hare: As a kid I was constantly making comic strips and writing stories. I really wanted to do something like that when I grew up. When it came time for college, I figured I better pick something practical but still creative – so I went into graphic design. I worked up to the position of art director for a sportswear company and then I started my own graphic design business but in my spare time I continued to make cartoons and play with story ideas. I just couldn't let it go! I decided to attempt a career shift and work at becoming an children's book illustrator and writer.

As to whether or not the books are for children or accidentally catch the interest of children: I recall an interview with Maurice Sendak where he said – paraphrasing here – that he didn't make stories for children, he made stories for himself that kids happen to like. That really nails it. [Hare refers to an interview with TIME Magazine]

How do your research, painting and communication methods differ from your previous work as a graphic designer?

My communication methods are definitely influenced by my graphic design training where one has to be very conscious of how the eye is being led through a composition and what elements are being emphasized. I also rely on my childhood love of making comic strips. In comic strips you have a few panels to get an idea across so you have to be very economical with the art. As far as research goes, the big difference is I'm generally excited by the subject when making a story. If I'm into a subject I'll research it in depth for fun. If I'm not that interested, as was often the case for commercial work, then my reading comprehension seems to evaporate and it becomes a real chore. I suppose that's true of most folks.

Painting is another story. I never really painted much as a kid or even as a graphic designer. I happened to pick up painting as life started to go really sideways. I'm so thankful because I'm not sure how I would have gotten through without the cathartic release it provided. Only later did I realize painting was the missing piece that gave me the confidence to make a real push at illustrating stories.

Who or what helps you the most to be creatively productive?

Winter and rainy days for one. When it's nice out I find it incredibly difficult to sit still and paint or write. Getting out of my comfort zone also tends to produce results...unless that means staying inside and sitting still on a beautiful day.

The policies to deal with COVID-19 have shifted our communication to the online world. It is not possible for you to present your books in groups of children. How do you manage to get feedback, are you in touch with the people who read your books with their children or mentees? Or is the feedback from your family and friends, or from your publisher more important to your working process?

I don't typically seek out a lot of feedback once a story is published. Perhaps that's because I'm sensitive and I fear it may affect how I make stuff in the future. Regardless, a certain amount of feedback is unavoidable and for sure beneficial. Even the critical feedback – because if I'm really bothered it probably means the person is pushing on something that I knew was a problem. If I'm not bothered I suspect it indicates I wouldn't have done that part differently and I remind myself it's not for everyone. I do occasionally have people reach out via email saying how a story affected them, their children or their class – and I love that!

Now I am interested to know what the differences are between your work on Field Trip to the Moon and Field Trip to the Ocean Deep, where you probably were supported by your publisher from the beginning: How long was each process from initial story idea to publication? What was easier, what was more complicated while working on the second book – the research process, the content, the character design, the illustrations, or the communication process with your publisher?

Initial idea to publication was longer with the Moon because we had to find a publisher willing to take a chance on an unknown author illustrator. But Moon was also far easier. The idea kind of flowed out, and I had confidence in it. Deep felt more complicated. Not only because it was my second book – which I've come to find out can be famously difficult – but also because it was a sequel to Moon which meant I couldn't use any random idea I'd been rolling around in my head. It needed to feel like a Field Trip book. Another reason it was difficult was because Deep was set at the bottom of the ocean and I wanted it to be very dark. I wasn't used to painting in such tones so the art took me longer to figure out as well. The whole process was a marathon that I knew had to get through and I'm very pleased with how the end result fits in as a Field Trip book.

What inspires you the most when inventing a new world?

Imagining myself there as a child. I imagine what the topography is – the peaks and valleys. What is safe? What is dangerous? What would I want to gently poke with a stick? What would I want to turn over and examine? Where could something be hiding? Where could I hide if that something is not friendly? And believe it or not, science inspires me. These may be fantastical worlds but there are certain rules of physics I'll bend but not break. That doesn't mean the highly improbable can't happen!

Figures 2 and 3: The original version of the fishosaurus (figure 2) compared to the less threatening final version (figure 3) (Source: John Hare and John Hare's portfolio)

On your blog, you show early drafts of Field Trip to the Ocean Deep; some of them were much more dramatic than the illustrations published in the final version. Why did you decide not to include those earlier drafts? Did you think it would be too creepy for young readers?

Yes! The original draft for Deep was VERY different. I wasn't as concerned with hiding the kids' identities and the creatures were a bit more primal and intense – how I imagine the ocean to be! The problem was that while it felt like an interesting and exciting story, it didn't feel like the type of field trip story that Moon established. In the version you're referring to, giant amphipods (shrimp-like creatures), end up attacking the bus because they were attracted to its lights! As you can see, when I write to entertain myself I have to be careful not to neglect who my actual audience is! There was also a version where the encounter was with three giant cephalopods (an octopus, a squid and a cuttlefish). That was a close second to the one that got published.

Figure 4: Early draft with the school class exploring the ocean deep. The diving pods do not hide the kids' faces, with the school bus in the background (Source: John Hare)

What were your favorite characters or best-loved stories in your childhood?

My favorite story was Dr Seuss's The Sneetches. It's a great parable that has stuck with me throughout my life. In that same book was another story I was obsessed with called What was I afraid of? where a kid is terrified by a sentient pair of pale green pants with nobody inside them. I loved it. I also loved Frog and Toad are Friends – so gentle and great. The busy scenes and diagrams in Richard Scarry books would give me something to stare at for hours. And I also loved the Berenstain Bears. Truly my favorite characters were Calvin and Hobbes. I know they're not children's book characters but I would read and reread Bill Watterson's comic strip collections as if they were some kind of scripture. And while we're talking about comic strips I have to include The Far Side.

Whose works are most important for you nowadays?

I really love Shaun Tan's work. When I pick up a book like Rules of Summer I'm blown away by the art and have no idea what the next page will reveal. His work has an atmosphere that takes me away every time I view it. It's inspiring!

Thanks a lot for this interview! I wish you all the best for the future, and I look forward to many more (picture) books from you!

Figure 5: The cephalopods discover one of the kids. Unpublished draft. (Source: John Hare)